Is Mainstream Medicine Evil?

How Drugs Come to Market

This summarises the 10th chapter of Bad Science by Ben Goldacre: Is Mainstream Medicine Evil? The chapter explains the tricks used by pharmaceutical companies while they conduct expensive drug trials to make their products seem better than they are. Big pharma is one of the most distrusted sectors of the economy and modern healthcare. It is therefore important to understand how ‘evil’ they are to know how best to counter it.

The Journey of a Drug

- The idea for a drug - This might come from a plant molecule, a receptor that can be interfaced with in the body, a theoretical scientific breakthrough, etc.

- Animal trials - This is used to confirm that the molecule you have in mind does what you think it does and that it doesn’t kill the animals.

- Phase I human trials - Done on healthy young people to see the side effects and understand how it is excreted from the body.

- Phase II human trials - Done on people with the illness you intend to treat. The aim of this stage is to see if it does treat the illness and work out the proper dosage.

- Phase III human trials - A randomized, blinded trial on thousands of patients compared against a placebo or other comparable treatment.

If your Phase III trial is successful, you need to conduct several similar trials and then you can apply for a license for your drug. After the drug goes to market, you should continue conducting trials and hopefully, other entities that aren’t related to the pharmaceutical company do replication studies and keep an eye out for side effects reported by patients.

However, drug trials are expensive and 90% of clinical drug trials are paid for by the pharmaceutical industry meaning they exert a lot of influence on what gets studied and published. As a result, diseases that are considered ‘unprofitable’ to treat are neglected. These include rare diseases or those that are only prevalent in developing countries e.g. sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis). Other conditions/treatments are not studied because they can’t be patented. For example, magnesium sulphate has been used since 1906 for the treatment of eclampsia(a leading cause of maternal death); but research into it wasn’t done until 2002 when the WHO funded a study. The Global Forum for Health Research estimates that only 10% of the world’s health burden receives 90% of total biomedical research funding.

Drug trials by pharmaceutical are more likely to produce a positive outcome for their own drug. Since their core audience is made up of doctors, they need to come up with smarter tricks than quacks that market to the general population like homoeopaths.

Sleight of Hand

These are some of the tricks you could pull to all but ensure positive results from your drug trial:

i. Test it in a healthier population.

- Study it in a population of young people with the disease instead of old people with multiple conditions who are on multiple drugs. This will make the research less applicable to the actual people that the doctors are prescribing for.

ii. Compare the drug against a useless control.

- When a drug is compared against a placebo, it is likely to give overtly positive results. However, most people don’t care whether your drug is better than a sugar pill, they care whether it is better than the best available treatment.

iii. Use an inadequate dose of the control drug.

- If you are required by law to control against another drug by a competitor, you could dose it incorrectly. Giving a smaller dose makes the drug seem worse than it is; giving a larger dose increases the side effects. Other trials have administered the competing drug incorrectly e.g. giving a drug orally when it should be given intravenously.

iv. Don’t ask about side effects.

- Or be careful about how ask. For example by giving a checklist of ‘possible’ side effects instead of asking an open question. This is how SSRI trials hid the sexual side effects of the anti-depressants.

v. Measure surrogate outcomes.

- Instead of measuring real-life outcomes like pain or death, measure a ‘surrogate outcome’ for your drug to attain like cholesterol reduction. If your drug is supposed to reduce cholesterol levels and therefore prevent cardiac deaths; don’t measure the rate of deaths. Measure cholesterol levels and then imply that their reduction leads to a reduction of deaths.

vi. Draw attention away from negative results.

- If despite all your efforts you still get some negative results, don’t draw attention to it by putting it in a graph. Mention it briefly and then don’t consider it when making your conclusion.

vii. Don’t publish negative results.

- If your results are completely unsalvagable, put them in a drawer and never mention them again. Or you could do more trials with the same protocol, hope they throw out positive results and bundle them together to undercut the negative results.

Lies, Damned Lies and Statistics

This is how to torture the data enough to give you positive results.

- Ignore the pre-established protocol. - Throw your data into a data analysis tool and report any correlation as positive causation.

- Play with the baseline - If the treatment group is doing better than the placebo group at the beginning of the study, leave it be, but if the placebo arm is doing better, adjust for that in your analysis.

- Ignore dropouts - Dropouts out of a study are more likely to be doing worse or have had terrible side effects. Do not include them in your analysis.

- Clean up data - If there are ‘outliers’ that make your drug look bad, delete them; but if they make your drug look good, leave them in.

- Let the results determine your timeline - If the difference between your drug and the control becomes significant at 6 months, for example, stop the trial. Otherwise, extend the trial till you get what you want.

- Torture the data - Check if specific subgroups happened to perform well in the study e.g. Chinese women aged 52 to 61. Report this a significant result even if it’s just random.

How Do We Know That This is an Industry-Wide Problem?

Systematic reviews of the literature have found that studies funded by pharmaceutical companies are 4 times more likely to give favourable results than independent studies. Despite having seemingly impeccable methodology, industry studies show that every painkiller is better than every other painkiller. How does this happen?

Publication Bias

Positive results are much more likely to be published than negative ones. Here is a statistical exercise to prove this.

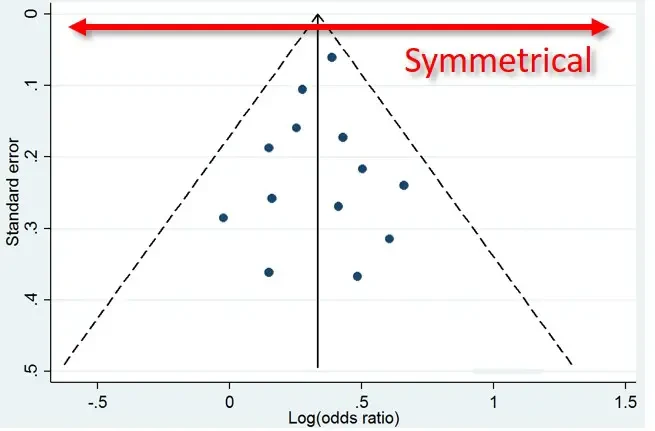

If there are lots of trials in a field, you would expect the results to cluster around the true answer. The bigger studies with better methods would be close to the truth while the smaller ones would be all over the place since they’d be thrown off by outliers. These statistical outliers should be both negative and positive. This can be shown through a funnel plot as demonstrated below.

If there is no publication bias, there should be an inverted funnel where the big accurate trials cluster around each other at the top of the funnel and the small inaccurate trials gradually spread out to BOTH the right and left as they become increasingly inaccurate (both positively and negatively).

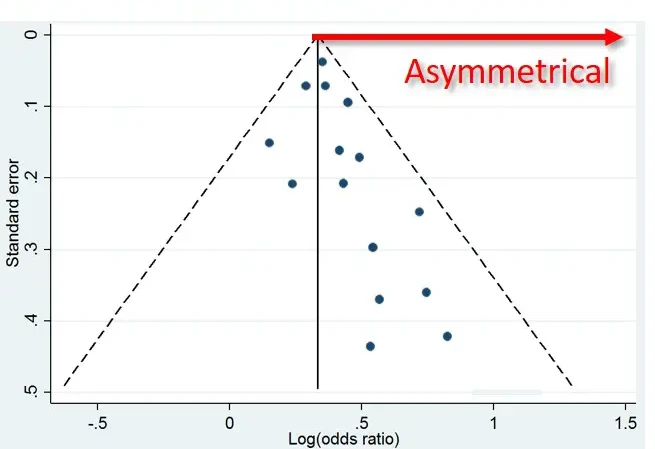

However, if there is a publication bias, the results will be skewed as the smaller negative studies are missing but the smaller (spuriously) positive studies are published. This has been demonstrated in many medical fields.

Duplicate Publication

Drug companies don’t just hide negative results. They also publish positive results several times, in different places, in different forms so it looks like there are lots of different positive trials. This leads to an overestimate in the efficiency of the drug in the eyes of medical practitioners.

Hiding Harm

Sometimes pharmaceutical companies just straight up hide evidence that their drugs are causing harm to patients. This can be due to neglect and publication bias. But there are examples of the side effects of drugs being swept under the rug and ignored for decades.

Authors Forbidden to Publish Data

We have several accounts of authors and researchers who have been bullied or pressured not to reveal information about studies they have performed funded by the pharmaceutical industry.

The Simple Cheap Solution

The author has a simple proposal to solve almost all of these problems. The intervention is a clinical trials register, public, open and properly enforced.

If you wish to do a study, you would be required to pre-publish its protocol i.e. what you are going to do in your trial, what you’re going to measure in how many people and for how long. This would take care of the ‘moving the goalposts’ tricks pulled by pharmaceutical companies AFTER they have the results of the study. If you registered a study and conducted it, but did not publish the results, that would stick out like a sore thumb. Everyone would (rightfully) assume you had something to hide.